4 Brands That Used Their Unique Value Propositions (UVPs) to Grow Profits

Learn more about what a UVP is, where the traditional definition fall shorts, and how McDonald’s, Domino’s, Salesforce, and Hubspot used UVPs to grow their reputations and their profits.

Branding is based on the concept of singularly.

Which means that for your brand to thrive or even dominate in its market category, it must be known for something singular.

That “singularity” is otherwise known as your brand’s unique value proposition (UVP).

Read ahead to learn more about what brand UVPs are, where the traditional UVP definition falls short, and how four global brands grew their profits by focusing on creating unique value for their customers.

The traditional definition of a unique value proposition (UVP)

A brand’s unique value proposition is typically defined as:

A concise statement that names the differentiated trait, characteristic, or offer that makes a business special, amongst competitors, in the eyes of its specific audience segment.

Your brand UVP is the “special sauce” that only your business can bring to the market.

It’s the thing customers should know you for first because you’ve proven you can do it better than anyone else–and more reliably.

In sum, it’s your competitive advantage.

Your moneymaker.

The more focused your brand UVP is, the more memorable you’ll become to your target audience.

The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding, co-authored by Al Ries and Jack Trout—the men who invented and popularized the concept of brand positioning—say customers prefer that a company’s UVP be narrow in scope and distinguishable by a single word.

For example:

Kellogg’s is known for its cereal.

Monday.com is known for it’s project management capabilities.

The more focused your value creation efforts are, the easier you’ll be to remember.

“If you want to build a powerful brand in the minds of consumers,” Rise and Trout say, “you need to contract your brand, not expand it.”

Here’s what the standard UVP definition fails to consider

The challenge with the common UVP definition is that it places emphasis on what we say makes us special or unique, rather than the unique and specific value we actually commit to providing to customers.

The traditional definition here again:

A concise statement that names the differentiated trait, characteristic, or offer that makes a business special, amongst competitors, in the eyes of its specific audience segment.

See how the UVP is positioned to be a communication tool rather than a strategic business tool?

This nuance shifts our attention away from what a UVP is fundamentally designed to help a business achieve: stay focused on providing unique value to customers… in order to become profitable.

Profitability is the real Oz behind the UVP curtain.

Because to become profitable, you must consistently deliver value to your customers.

Which means UVP creation is much more than a marketing exercise that yields a UVP statement.

It’s a business conversation about value creation—and everything that might add to or erode your value creation efforts, including but not limited to: your business’s organizational structure, digital infrastructure, product roadmap, user experience guidelines, and brand culture.

Of course, marketers are well suited to lead and champion the UVP conversation. Researching market whitespace, analyzing consumer trends, and understanding customers’ needs and pain points is where we can shine from a development standpoint. As for implementation, we’ve got countless tricks up our sleeves.

But for a UVP to really do its job, all company stakeholders must adopt a value-focused approach to doing business.

4 brands that prove value-focused business strategy pays off

Now that we know more about the real job of a brand UVP, let’s proceed with a slightly revised definition:

A unique value proposition is the differentiated and focused value a business commits to providing to a specific audience segment in order to become profitable.

As you socialize the idea that UVP creation is really a conversation about value creation and profitability, rely on the following four use cases as you need them.

McDonald’s, Domino’s, Salesforce, and Hubspot are not only heavyweight champions in their respective market categories, but they’re the creators of their market categories.

Each proves that when you build a business operation to provide unique and focused value to a specific audience segment, big things happen.

You’ll see in the case of McDonald’s and Domino’s, they didn’t know what their real UVP was when they first opened. It wasn’t until they observed customer behavior, analyzed their sales, and reassessed their target audience that they were able to zero in on, define, and leverage their UVPs for profitability.

Salesforce and Hubspot, on the other hand, charged into their industries with a defined purpose, aiming to revolutionize their markets. By prioritizing value creation from the outset, they rapidly accelerated their growth trajectories.

Please note: these stories focus on each business’s early-day UVPs and audience segments. They are not meant to capture each brand’s current UVPs or target audience.

McDonald’s

McDonald’s wasn’t always known for its Happy Meals and Big Macs. It actually started out as a barbecue joint that also sold hamburgers. And tamales. And PB&J.

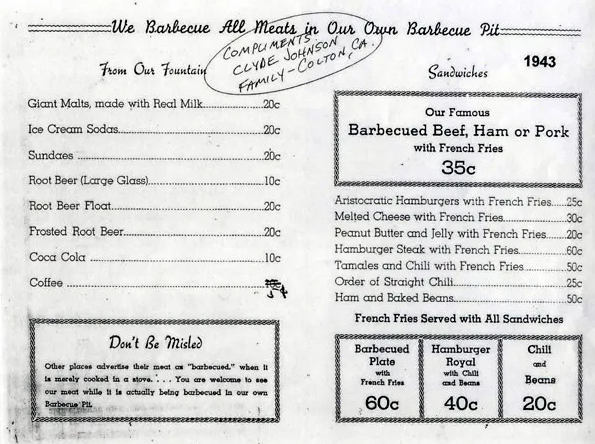

Their original UVP was “We Barbecue All Meats in Our Own Barbecue pit.”

Black and white version of original McDonald's menu which features PB&J and tamales. Source.

But over time, they realized that the more they pushed their barbecue business, the more hamburgers they sold.

They observed that the unique value they were providing to their customers wasn’t slow-cooked bbq (even though that’s where they were investing a majority of resources), but affordable hamburgers (no cheese) that could be served hot and fast for families on the go.

So they decided to close the business for three months to become a restaurant known exclusively for serving hot and tasty hamburgers (and fries, shakes, and pie) at an affordable price with little wait time.

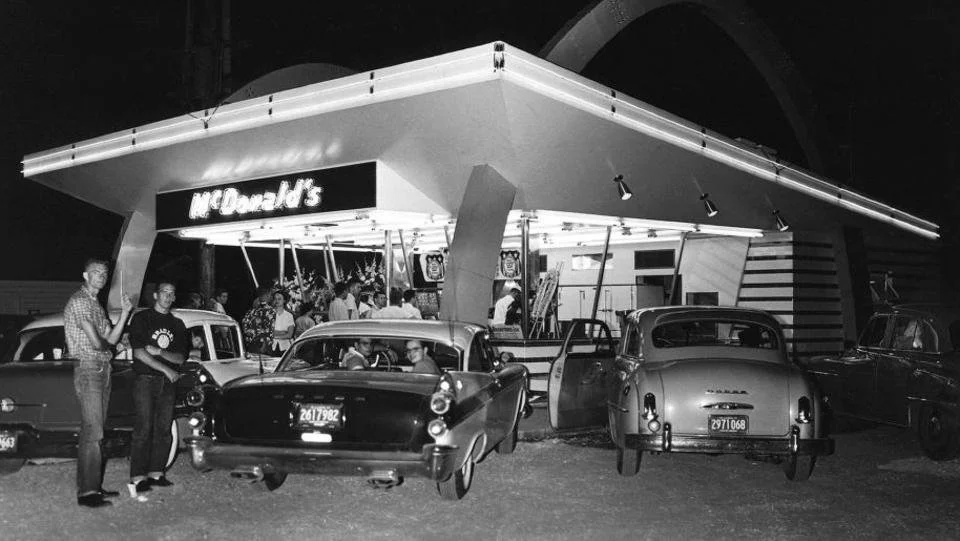

The McDonald’s brothers stand outside a billboard promoting the revamped version of McDonald’s, a “drive-in hamburger bar.” Source.

In redefining their UVP and, McD’s didn’t just change their menu; they revolutionized their operational strategy to focus on speed, lower prices, and volume.

When they reopened, it was as a self-service restaurant where customers now placed their orders at the window.

They fired their carhops and dishwashers, replacing their silverware and plates with disposable paper wrappings and cups.

They developed the infamous “Speedee Service System,” which “mechanized” the kitchen to become more efficient and ultimately led to franchising opportunities.

By consistently delivering on their promise of quick service and low prices, McDonald’s has become a ubiquitous name in the fast-food industry, proving that a well-defined, customer-centric UVP can drive significant business success and market leadership.

Domino’s

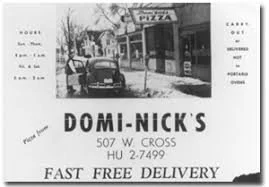

Before Domino’s was called Domino’s, it was a single-store, college town pizzeria called Domi-Nicks.

Located near Eastern Michigan University (EMU), Domi-Nick’s sold pizzas and sandwiches, and was owned by a man named Tom Monaghan, who bought it from the original owner in 1960, and became the sole proprietor in 1961.

Domi-Nick’s unique value proposition was hot and fast pizza delivery. It was a service no one else in the area offered. What elevated this UVP was the corrugated pizza box Domi-Nick’s pizzas were delivered in.

Monaghan and his brother (who co-owned Domi-Nick’s with Tom for less than a year) recognized that traditional pizza boxes weren’t sturdy or insulated enough to withstand the rigors of delivery.

So they invented a new type of pizza box–the corrugated pizza box–that would help them make good on their promise of hot, fast delivery.

(Because of this innovation, they’d go on to be recognized as the inventors of the pizza box.)

Ad from Domi-Nick’s promoting their UVP: fast, free delivery. Source.

But despite the novelty of their offer, and much to Monaghan’s chagrin, Domi-Nick’s was still operating at a loss.

The situation was so dire that he considered selling the place and getting out of the pizza game completely. But he stayed, determined to make Domi-Nick’s successful.

So how did Monaghan turn a floundering pizzeria into one of the best-known pizza franchises in the world?

First, he evaluated which items on his menu were making him money and which were costing him money.

He discovered he was losing money on his smallest-sized pizzas. They took the same amount of time to make as the larger pizzas, but brought in less revenue. So he cut them from his menu, despite their popularity.

Next, he evaluated his target audience.

By cross referencing his sales against where pizzas were being delivered, he discovered that EMU college students ordered pizza from Domi-Nick’s the most.

With this realization, he revamped his business strategy and marketing efforts to focus on the college market.

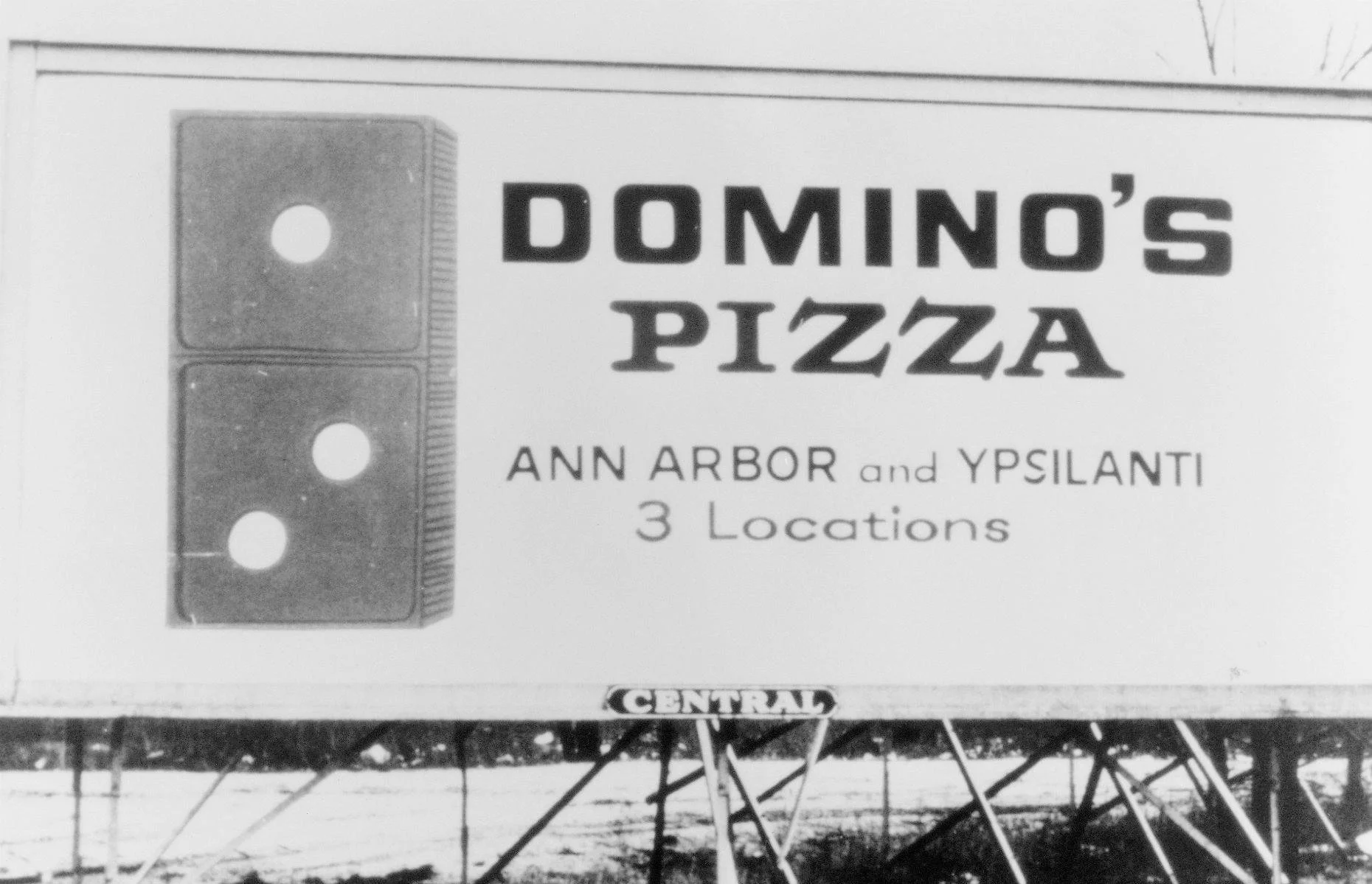

By 1965, Domi-Nick’s was turning a profit. Monaghan bought two more pizzerias. One was strategically located next to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and the other by the Michigan State University campus.

In that same year, he united his three stores under the single banner of Domino’s to build memorability and trust with his customers. That’s what the three dots in the Domino’s logo represent: his first three stores.

A billboard promoting Domino’s new name, logo, and locations; the dots on the domino represent all three stores . Source.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Worth noting: Domi-Nick’s offered fast free pizza delivery from the very beginning–pre Domino’s. And yet they were still operating at a loss.

It wasn’t until the UVP was presented to the right audience–college students–that it began to work as a profit accelerator rather than a simple marketing tagline.

Salesforce

In the 1990s, customer relationship management (CRM) software was a nightmare for customers. It had to be installed on-premise, which meant high upfront costs, lengthy implementation times, and complex maintenance requirements.

At the time, Oracle was a CRM market giant. Marc Benioff, a vice president there, took note of this accumulating list of flaws.

He began to imagine something different.

What if CRM tools could be delivered over the internet? Customers could say goodbye to costly installations and extensive IT upkeep, and trade it all in for powerful, user-friendly software that was as easy to use as a website.

So in 1999, he left Oracle. He founded Salesforce in the same year.

By 2000, he and his partners started working on the very first version of the Software as Service (SaaS) Salesforce CRM, where services were all available on the cloud.

They went to market with a focus on serving small and medium sized businesses (SMBs), who typically lacked the resources and expertise to implement traditional, on-premise CRM solutions.

First Salesforce office in Telegraph Hill, San Francisco. Source.

In the same year they launched, and to help popularize the idea of internet-based software (and to build awareness around the brand), they staged a fake protest in front of a major competitor’s user conference, hiring actors to carry signs with Salesforce’s new “The End of Software” tagline.

The protest earned them the media attention they were looking for. The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Businessweek, and others were all taken by the story of the startup willing to go toe-to-toe with industry giants to better serve its customers.

An image of Benioff getting interviewed at the 2000 “End of Software” protest. Source.

But there’s a twist to this story.

While Salesforce used the innovation of the SaaS model to capture attention and build brand awareness in their early days, it wasn’t meant to serve as their long term value proposition for customers.

Benioff and his leadership team knew that SaaS was the way of the future, and that competitors would be jumping on the bandwagon soon enough.

So Salesforce focused on creating SaaS CRM features that other CRMs tools weren’t designed to do: automate the customer’s sales cycle.

Traditional CRM systems often focused on data management and basic contact organization, rather than providing comprehensive sales automation features.

Salesforce’s early CRM solution, on the other hand, included features like lead management, opportunity management, sales forecasting, and automated workflows to streamline repetitive tasks and processes, reduce manual effort, and increase efficiency.

You see, Salesforce wasn't content with just improving the traditional CRM experience.

They aimed to revolutionize it completely by addressing a CRM customer’s deeper needs: to create a more effective and efficient sales force.

By zeroing in on automation and sales efficiency, Salesforce delivered a unique proposition that met the genuine needs of the SMB CRM market, fostering both customer satisfaction and substantial profitability.

Hubspot

Before HubSpot's inception in 2006, the marketing landscape was dominated by outbound tactics—think cold calls, unsolicited emails, and intrusive digital ads.

It was a pay-to-play environment, which meant that with limited resources and expertise, small businesses were at a disadvantage compared to larger competitors with hefty marketing budgets.

Meanwhile, two business-focused MIT students–Brian Halligan and Dharmesh Shah–observed that the internet was changing how people shopped and learned. Consumers didn’t want to be interrupted by flashy popup ads while online; they wanted trustworthy, peer-approved information to help them make better buying decisions.

Halligan and Shah, running on the belief that technology should enable smaller companies to compete with larger companies, wanted to do something about it.

So they created and tested a thesis that acquiring “inbound leads”–i.e., leads who discover businesses through Google search, social media, and blog content–would be less expensive and easier to acquire than outbound leads.

They were right.

It wasn’t long before they officially launched Hubspot, an “inbound marketing software platform” designed to help small businesses create and manage content; improve their search engine rankings; capture and track leads with landing pages and forms; and engage their audiences on various social platforms.

Soon after, “inbound marketing,” as a concept and practice, was embraced by the global marketing community.

Halligan and Shah literally wrote the book on inbound marketing. Source.

In interviews, Halligan and Shah have been clear that they chose their target audience before they chose their product. That’s why Hubspot was such a home run. They built it to solve a specific problem for a specific audience that no other competitor was solving.

At the time of this writing, Hubspot is valued at $31 billion. Their success proves that the fastest way to grow and thrive as a business is to focus on creating real value for real people.

Conclusion

The stories of McDonald’s, Domino’s, Salesforce, and HubSpot demonstrate the transformative power of a well-defined unique value proposition (UVP). Each brand found their distinct niche by focusing on their target audience and delivering unparalleled value, resulting in significant growth and market leadership.

McDonald’s shifted from a local barbecue joint to a fast-food giant by reconfiguring its business operation, and menu, to give families more of what they wanted: affordable burgers served hot and fast.

Domino’s created a brand new market category–pizza delivery–by promoting hot pizza delivery to the audience that would appreciate it the most: college students.

Salesforce exploded in popularity (and profitability) by creating a customer relationship management (CRM) software experience that solved the customer pain points bigger CRM players ignored.

And HubSpot democratized marketing by giving the little guys an affordable way to compete with larger competitors.

These examples highlight that a UVP is more than just a marketing statement; it’s a strategic business tool that should permeate every aspect of an organization. By committing to delivering unique and specific value to their customers, these brands not only grew their profits but also established strong, memorable identities in their respective markets.

As you work to define and implement your own UVP, remember that its true power lies in its ability to guide business decisions and operations, ensuring that every effort is aligned with creating real value for your customers. When done right, a UVP is not just a promise—it’s a pathway to sustained success and profitability.

Getting started

Do you struggle to have meaningful conversations about UVPs in your organization?

I’m here to assist!

To learn my proven, step-by-step UVP creation and rollout process—designed to maximize marketing impact and accelerate business growth—email me at ashley@peoplethebrand.com or send me a note on LinkedIn. Look forward to connecting!